Abstract

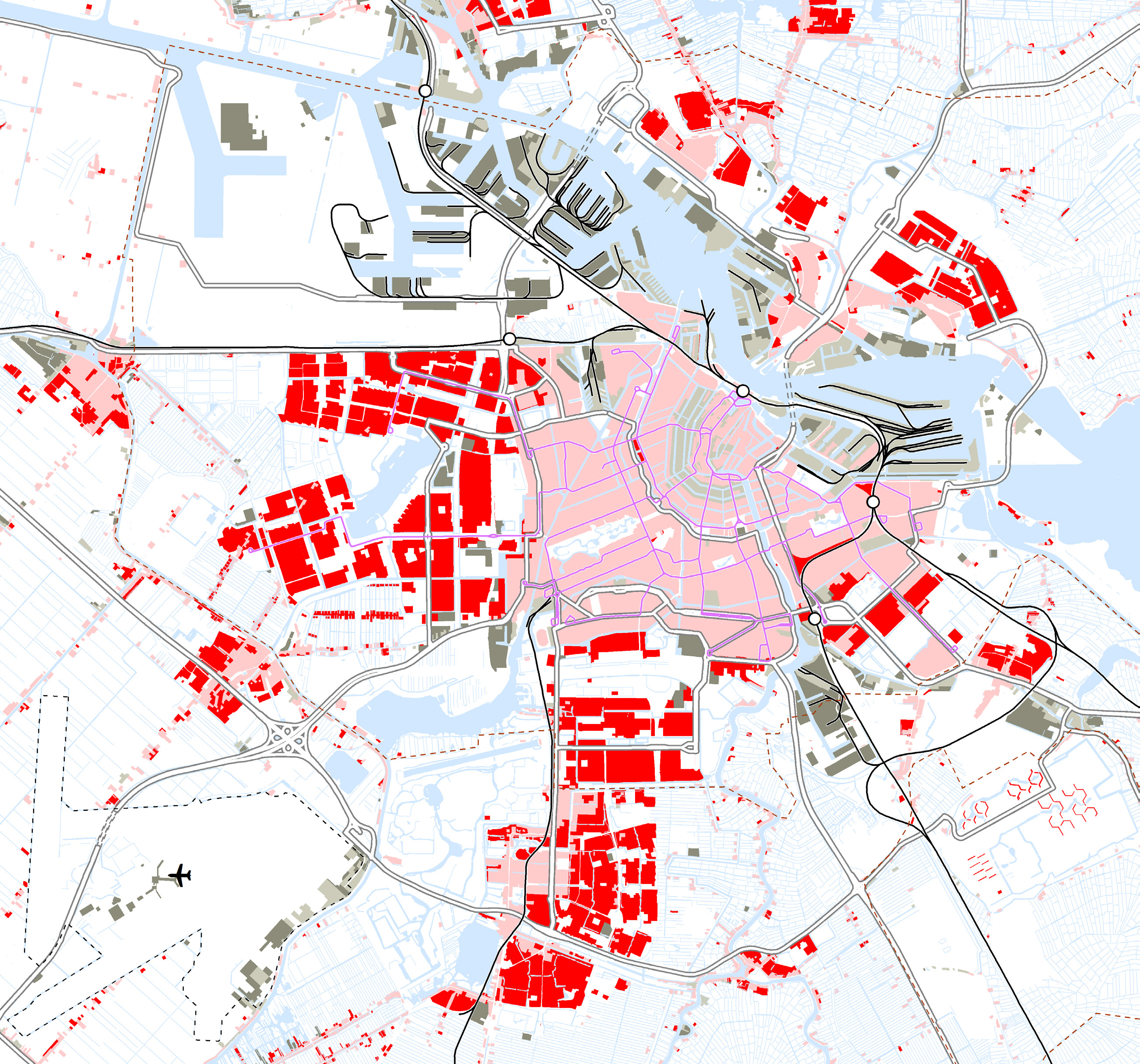

Around 1850, Amsterdam was surrounded by water, on a tongue of land between the River IJ to the north, the Zuiderzee (then still an inlet of the North Sea) to the east and the Haarlemmermeer lake to the south-west. The Singelgracht canal, dug in the seventeenth century, still marked the boundary between the city and the countryside. Although the fortifications no longer served any military purpose, landward access to the city was still controlled via the city gates, so that municipal excise taxes could be levied. The western and eastern port islands were also protected by docks, and the River Amstel could be sealed off near the Damrak canal. Besides the port and work areas located inside the city boundaries (marked in grey) there was a large unbroken work area to the west of the city between the Singelgracht and Kostverloren Vaart canals, with large numbers of industrial mills.

In the previous decades major infrastructural works were commissioned by the government in order to strengthen Amsterdam’s position as a trading centre. The construction of the Rijksentrepotdok (‘National Warehouse Dock’) on the edge of the eastern port area in 1827 gave the city a tax-free transhipment centre. The north-south water route was enhanced by the construction of the North Holland Canal in 1824 and improvements to the navigability of the River Amstel in 1825. The advent of the railways ended the centuries-long domination of water transport. The first line, between Amsterdam and Haarlem, opened in 1839, to be followed in 1843 by the Amsterdam-Utrecht line. Both lines ended at terminus stations just outside the Singelgracht canal.

The main public institutions were mostly located in the mediaeval part of the city. A new exchange building, the Zocher Exchange, had recently been built. In 1808 the city hall on the Dam square was turned into a palace by King Louis Bonaparte, and the exchange bank, the courthouse and the city council had to move to new premises. The city council was housed in Prinsenhof, in the former monastery and convent district, and in 1836 the Amsterdam courthouse moved from there to the Palace of Justice on the Prinsengracht canal.

The main social welfare institutions, such as the Burgerweeshuis orphanage and the Binnengasthuis hospital, had been built back in the seventeenth century on the former sites of monasteries and convents in the south of the mediaeval part of the city.

The only large green area, the Plantage, was located on the eastern side of the city, inside the Singelgracht. This contained the botanical gardens (created in 1683) and the zoo (1835), in between allotment gardens, timber yards, tea gardens and open-air theatres. Permanent construction was not yet officially allowed there. Large institutions such as the Orange-Nassau barracks and the prison with cells were built here and there on the former sites of bastions.

How to Cite

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2019 OverHolland

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.